occasional essays on working with words and pictures

—writing, editing, typographic design, web design, and publishing—

from the perspective of a guy who has been putting squiggly marks on paper for over five decades and on the computer monitor for over two decades

Wednesday, February 20, 2008

Thursday, February 14, 2008

A marginal note

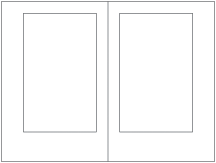

Here is a Book Design 101 picture:

Fig. 1

Figure 1 represents the ideal, classical page. The inner (gutter) margin is the narrowest, with the top margin equal or slightly larger, then the outside margin larger still, and finally the bottom margin largest of all. This is the way we are accustomed to seeing the page. Grab an old hardcover book from your shelf (the older the better), and lay it flat on the table in front of you, open to any page. The spine arches away from the cover so the pages can lay flat, and the pages resemble, to a fair degree, Figure 1.

Now look at a softcover book, a so-called trade paperback—that is, an expensive new book that may never have been issued in hardcover. I’m not referring here to the small mass market paperback you may have picked up at a supermarket or airport, but rather something larger, perhaps six inches by nine inches.

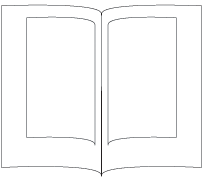

Open it up on the table in front of you. It’s permissible to hold it open with your hands or a weight. It looks something like Figure 2, doesn’t it?

Fig. 1

Figure 1 represents the ideal, classical page. The inner (gutter) margin is the narrowest, with the top margin equal or slightly larger, then the outside margin larger still, and finally the bottom margin largest of all. This is the way we are accustomed to seeing the page. Grab an old hardcover book from your shelf (the older the better), and lay it flat on the table in front of you, open to any page. The spine arches away from the cover so the pages can lay flat, and the pages resemble, to a fair degree, Figure 1.

Now look at a softcover book, a so-called trade paperback—that is, an expensive new book that may never have been issued in hardcover. I’m not referring here to the small mass market paperback you may have picked up at a supermarket or airport, but rather something larger, perhaps six inches by nine inches.

Open it up on the table in front of you. It’s permissible to hold it open with your hands or a weight. It looks something like Figure 2, doesn’t it?

Fig. 2

Because of the way most paperback books are bound (so-called perfect binding), the pages do not lay flat. Instead, they are pinched into the glued spine, and the text block curves into the gutter.

We’re all so used to this, that until someone looks at such a book with fresh eyes, as a client of mine did a couple of days ago, we hardly notice the discomfort in reading the curved text. When books were always issued first in hardcover editions, this design was fine. If the cheapskates who waited for the paperback were somewhat inconvenienced by the narrow gutter, publishers didn’t care.

But today the vast majority of books are issued first as trade paperbacks and are only issued in hardcover after they begin to gain some traction in the marketplace.

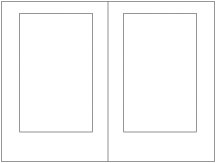

So why are we still designing as if the pages are going to lie flat for the reader? Well, because that’s how we designers were trained, for one thing. But let’s rethink this. The basic unit of book design, the two-page spread, sits there in front of us in our page layout software looking very much like Figure 1. But if we think for a moment about the conditions under which readers will encounter the book—something much like Figure 2—we can see that what we should do is widen the gutter margin substantially, to compensate for what will be lost in the perfectbound gutter.

I propose that Figure 3 should be what we begin with from now on, for books that will be marketed as trade paperbacks. It’s easy enough to generate new output files with the margins in Figure 1 if the publisher decides to issue a hardcover later. There’s no longer a good reason—given the way books are manufactured these days—to use the same book block for both editions. The savings are not sufficient to justify it.

Fig. 2

Because of the way most paperback books are bound (so-called perfect binding), the pages do not lay flat. Instead, they are pinched into the glued spine, and the text block curves into the gutter.

We’re all so used to this, that until someone looks at such a book with fresh eyes, as a client of mine did a couple of days ago, we hardly notice the discomfort in reading the curved text. When books were always issued first in hardcover editions, this design was fine. If the cheapskates who waited for the paperback were somewhat inconvenienced by the narrow gutter, publishers didn’t care.

But today the vast majority of books are issued first as trade paperbacks and are only issued in hardcover after they begin to gain some traction in the marketplace.

So why are we still designing as if the pages are going to lie flat for the reader? Well, because that’s how we designers were trained, for one thing. But let’s rethink this. The basic unit of book design, the two-page spread, sits there in front of us in our page layout software looking very much like Figure 1. But if we think for a moment about the conditions under which readers will encounter the book—something much like Figure 2—we can see that what we should do is widen the gutter margin substantially, to compensate for what will be lost in the perfectbound gutter.

I propose that Figure 3 should be what we begin with from now on, for books that will be marketed as trade paperbacks. It’s easy enough to generate new output files with the margins in Figure 1 if the publisher decides to issue a hardcover later. There’s no longer a good reason—given the way books are manufactured these days—to use the same book block for both editions. The savings are not sufficient to justify it.

Fig. 3

It may take a while for the people who judge design competitions to catch up, and I don’t suppose publishers will start changing their house styles right away. But I’m going to start down this path and hope others join me. I think it will make books more fun for readers again.

Fig. 3

It may take a while for the people who judge design competitions to catch up, and I don’t suppose publishers will start changing their house styles right away. But I’m going to start down this path and hope others join me. I think it will make books more fun for readers again.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1 Fig. 2

Fig. 2 Fig. 3

Fig. 3Monday, February 11, 2008

Books have gone from bad to wurst

Have you noticed lately that the books you buy—I mean books from major publishing houses—are full of typos and editing gaffes? I see this complaint often. I make this complaint myself from time to time.

There was a time in living memory (mine, anyway—maybe not yours) when it was unusual to find more than a couple of errors in a book of several hundred pages. Publishers took pride in putting out good books because they thought this built brand loyalty for their imprint.

But publishing, like other traditional craft-based manufacturing industries, was taken over by vulture capitalists, who replaced the old managers with cost-cutting MBAs.

Nowadays, publishers—even those with a well-polished reputation for producing high-quality books—are not in the literature business; they’re in the sausage business. They buy carcasses, pay meatcutters and wurstmakers, and crank out the sausage, hoping that the customers will buy based on the packaging and reputation for quality (but not take too close a look at the ingredients list) and then cook and eat the sausage without dissecting the raw product to look for peculiar bits.

Mostly, there isn’t much you and I can do about this, other than producing books outside the mainstream publishing industry and building up an appreciation for high-quality books.

There is one category where individuals can make a difference, though. If you teach a course—especially at the college level—and you are unhappy with the quality of the course textbook, say something.

Complaining to a publisher that their wurstmakers fell down on the job isn’t going to change the publisher’s process or business model; it will just lead to hiring different wurstmakers. But suggesting to the buyer that you switch to a different brand of sausage will catch the publisher’s attention. I guarantee it. Write a letter to whoever was responsible for choosing that textbook. Explain the problem with the quality, and suggest that a competing book from a different publisher be selected for the following year’s students. Send a copy of the letter to the president of the publishing company. Hit where it hurts—in the wallet.

There was a time in living memory (mine, anyway—maybe not yours) when it was unusual to find more than a couple of errors in a book of several hundred pages. Publishers took pride in putting out good books because they thought this built brand loyalty for their imprint.

But publishing, like other traditional craft-based manufacturing industries, was taken over by vulture capitalists, who replaced the old managers with cost-cutting MBAs.

Nowadays, publishers—even those with a well-polished reputation for producing high-quality books—are not in the literature business; they’re in the sausage business. They buy carcasses, pay meatcutters and wurstmakers, and crank out the sausage, hoping that the customers will buy based on the packaging and reputation for quality (but not take too close a look at the ingredients list) and then cook and eat the sausage without dissecting the raw product to look for peculiar bits.

Mostly, there isn’t much you and I can do about this, other than producing books outside the mainstream publishing industry and building up an appreciation for high-quality books.

There is one category where individuals can make a difference, though. If you teach a course—especially at the college level—and you are unhappy with the quality of the course textbook, say something.

Complaining to a publisher that their wurstmakers fell down on the job isn’t going to change the publisher’s process or business model; it will just lead to hiring different wurstmakers. But suggesting to the buyer that you switch to a different brand of sausage will catch the publisher’s attention. I guarantee it. Write a letter to whoever was responsible for choosing that textbook. Explain the problem with the quality, and suggest that a competing book from a different publisher be selected for the following year’s students. Send a copy of the letter to the president of the publishing company. Hit where it hurts—in the wallet.

Thursday, February 07, 2008

Monday, February 04, 2008

Jonathan Karp wants to have 12 bestsellers a year

Lynn Neary’s story on NPR profiles Twelve, a Hachette imprint headed by the former editor-in-chief of Random House, Jonathan Karp, who publishes one book a month and devotes serious resources to promoting that one book. It’s an interesting gamble and an interesting interview. Check it out.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)